TUM alumna Nora Eibisch - here in the workshop for scientific instruments of the Deutsches Museum in Munich - loves to reconstruct a functioning system from the many individual parts of old complex machines (Image: private).

“Technical artefacts have or had a role for a distinct purpose“, she explains. Conservators have to unlock this purpose. “Here, for example the signs of wear are important. They indicate which wheels have been turned more than others, and which levers have been pulled very frequently.”

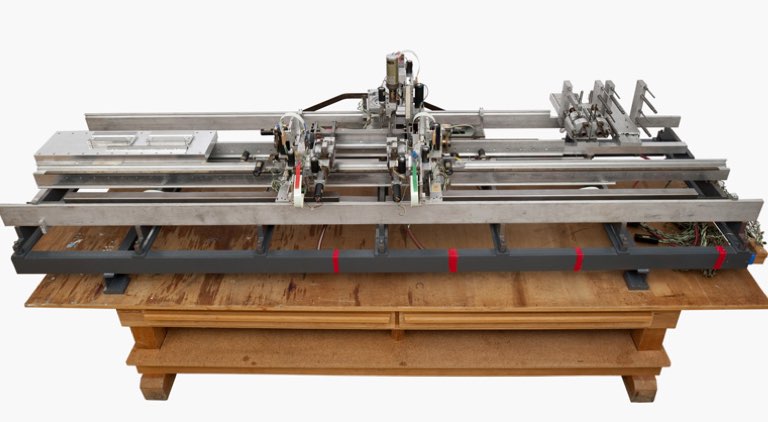

That way – after studying Restoration, Art Technology and Conservation Science at TUM – she reassembled a complete system from the fragments of one of computer pioneer Konrad Zuse’s machines: Nora Eibisch did research at the Deutsches Museum for her dissertation and restored Montagestraße SRS 72 on the basis of Zuse’s sketches.

“Zuse’s main idea was to develop microscopic technical systems, which act in the same way as biological cells”, she explains. As early as in the 1940s he successfully implemented his first designs of automated calculation machines, and based on that imagined a future in which artificial intelligence defines our lives, says Eibisch: today, many of Zuse’s visionary ideas are grouped under the heading of ‘digitalisation’.

So in 2010 the doctorate student stood in front of a multitude of individual parts of the complex trailblazer machine and figured out which parts go together in which way and how they could be fitted together to form a functioning ensemble. An incredible feat.

Her studies taught her to “ask the right questions – which still contributes positively to my life”, Eibisch says. And she enjoyed the “organised space for development”: “The foundations were put down during my undergraduate studies and building on that I was able to develop freely as a postgraduate”, she explains. Her work brought her to Deutsches Museum first and later to Silicon Valley, to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, where she was involved in various projects.

Nora Eibisch has written her doctorale thesis on the restoration on Konrad Zuse's Montagestraße SRS 72; the assembly robot is part of the collection at Deutsches Museum (Image: Deutsches Museum).

My dream is to restore this machine from its 765.000 individual parts.

Nora Eibisch is dreaming of restoring this calculating machine: “This machine with its more that 800km of cables connecting more than 765.000 individual parts, 3500 relays amongst them, is incredibly complex,” she explains. “For 15 years Mark I was running non-stop and must have made quite a lot of noise.”

Yet, it could do less than a modern-day calculator. “Imagine you stand in front of this machine and give it a task, such as the calculation of a parable, and watch this machine cracking and humming and take a few hours to produce a result on a punch tape, which your smartphone can give you in a matter of seconds plotted in a chart. This gives you an idea how rapidly and unpredictably technology is going to develop.” Understanding the technological development’s beginnings and comprehending them in their historical dimensions is the challenge conservators for technology like Nora Eibisch are facing.

The entire interview with Nora Eibisch is available in the TUM Community Blog. As an Alumni of TUM you can login here.

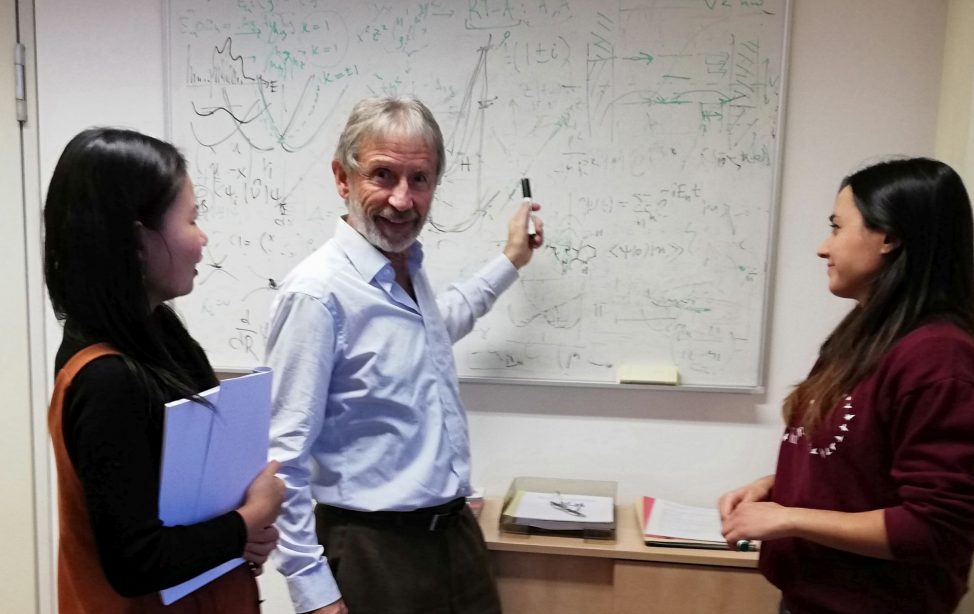

Dr. Nora Eibisch (Image: private).

Diploma in Restoration, Art Technology and Conservation Science 2009, PhD 2015

After her Diploma in Restoration, Art Technology and Conservation Science, Nora Eibisch did a PhD with Professor Erwin Emmerling.

For her thesis she restored and reconstructed “Montagestraße SRS 72“ by Konrad Zuse and as a result was awarded the TUM Board of Trustees PhD Price in 2016. As her PhD supervisor emphasises in his laudation, her thesis is “exemplary for what can be achieved with committed restoration”.

In 2017 the trained carpenter moved to Palo Alto with her family to work on several projects at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. Today, she is living in Berlin with her two kids and her husband Christoph Lippert (Bioinformatics 2008).