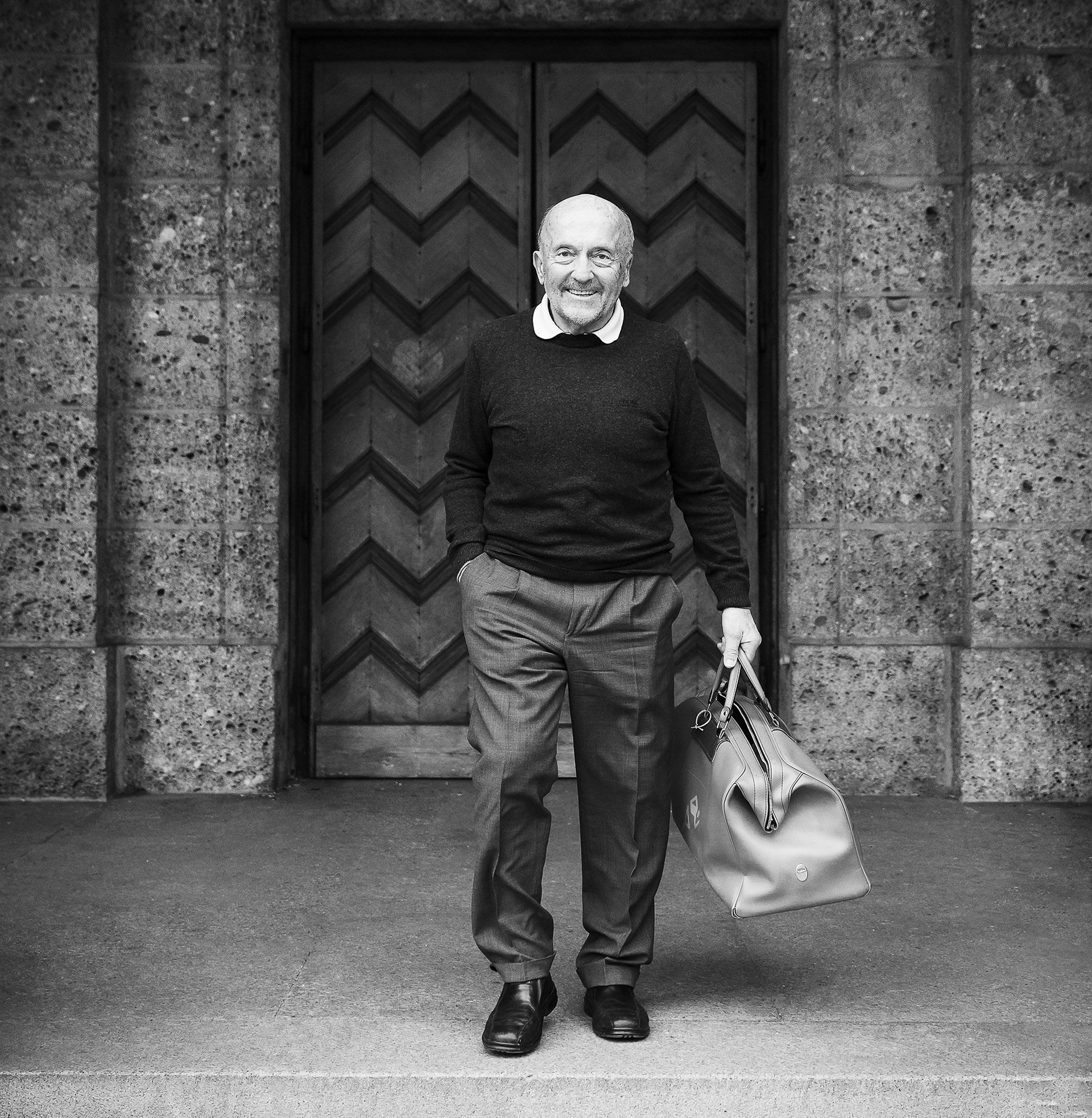

Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM.

We conducted the following interview with Klaus Wolfermann in summer 2018. Klaus Wolfermann passed away on December 18, 2024 at the age of 78.

Suddenly everything felt completely different. I was no longer just one of three up there – I was standing on top of the podium. The national anthem began. A shiver ran down my spine. Even today, when I talk about this moment in schools or at lectures or see pictures from that time, this feeling stirs a little bit within me.

When did your fascination with sport begin?

My father was a blacksmith and also a successful gymnast. He always dragged me along with him to gymnastics halls. That’s how I caught the sporting bug from him. From then on, that was my lifeblood. I wanted to find out what natural abilities I possessed and how far I could get with them. I did gymnastics until I was around 14 or 15 years old. Then I also started handball. It was already clear then that I had a strong throw. And in athletics I first devoted myself to the pentathlon and decathlon, then later to the javelin throw.

Was this the reason why, after leaving school at the Bavarian Sports Academy, which was integrated into TUM in 1972, you trained to become a freelance sports teacher?

I had previously trained as a toolmaker in Nuremberg. During my training I also attended school to further my education. At some point I realized: this profession is good, but it might impede my progress in sports. So, I set myself a new goal: I wanted to study to become a sports teacher in Munich. I started that in 1965. And fortunately, at the same time, my athletic abilities also grew.

I barreled through like a madman.

A lot of luck and also stamina. After completing my studies, I got a job as a sports teacher at SV Gendorf. There I was able to develop my abilities not only in terms of my career as a teacher but also as a competitive athlete. I worked many, many hours a week. But I was able to arrange my working hours so that I could train twice a day: two hours in the morning and between two and two and a half hours in the afternoon.

That sounds exhausting.

The volume was heavy. I had days when I was working 14 hours and then going to training. I was not home before 10pm. It amazes me now that I managed to endure this. But I can say that this is one of the gifts that God has given me: endurance, insane persistence – when I’ve really got my teeth into something like a terrier, then I do it right, come hell or high water.

With success! In 1968 at the German Athletics Championships you qualified for the Olympic Games for the first time.

I became the German silver medalist and that qualified me for the Mexico Olympics. It was great to meet so many athletes from all over the world, to watch them train and to learn from them. Unfortunately, over there I only achieved thirteenth place in the qualifying round and was therefore eliminated – the first twelve went on.

With his gold medal at TUM. Olympic champion Klaus Wolfermann brought his most valued possession with him to the interview at his alma mater (Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM).

I knew the next Olympics would take place in Munich – my hometown, if you like. I wanted to be right up there at among the best. That was the ultimate goal for me. So we planned those four years meticulously. I always wanted to dive straight into the lions’ den, to go where my opponents were competing. So I went to the big competitions in Helsinki, Stockholm, Oslo and Riga – where the big international events were happening.

How successful were you in these competitions?

It’s not like I would have won there in any case. I wanted to test myself, wanted to see where others were making mistakes, where their weaknesses and my strengths 30 were. In the early years it often was a bit of a struggle. A lot of the time I just wanted to fly back home. But I knew that I had to get through it. It is only way I could learn and then somehow find my own way.

The year before the Olympic Games in Munich was the test year. Things weren’t looking so bad. I had worked my way up through the rankings and improved the German record three times that year: 80, 85 and then 87 meters, all world class performances at the time. But the world record was over 90 meters! And this world record was held by a man who had already won the gold medal in Mexico: Jānis Lūsis, a Latvian athlete. I took a lot of pictures of him during these preparatory years. He was my idol. He had won all competitions in the year before the games. He had thrown the world record of 93.80 meters a few times – a huge distance. For me, unattainable.

Still, you managed to beat him. How?

My coach warned me not to do any more training than we had agreed in the training plan. But I couldn’t stop myself. My training volume just got bigger and bigger. This happened because I was just really enjoying it. I kept increasing it bit by bit. I just wanted to do it and I was having a lot of fun. At the same time, I listened to my body very carefully – you can have an incredible degree of control over your body for a certain amount of time. One and a half weeks before the Olympic Games, there was a small evening competition here in Munich. That’s the first time I threw over 90 meters.

That was already getting close to the world record.

I couldn’t believe it at first, although I knew that I had thrown the javelin well. You feel that when it’s out there in the air you are almost controlling it remotely. It went 90.24 meters that time. Afterwards, a woman came up to me with her daughter and wanted an autograph. It was an amazing feeling – I actually wrote down the wrong distance: instead of 90.24 meters, I wrote 90.48 meters.

Seriously? That’s your Olympic distance!

Unbelievable the kind of strange coincidences that can happen. But it was somehow an omen too. Everything was just right. And then there was the matter with the clock.

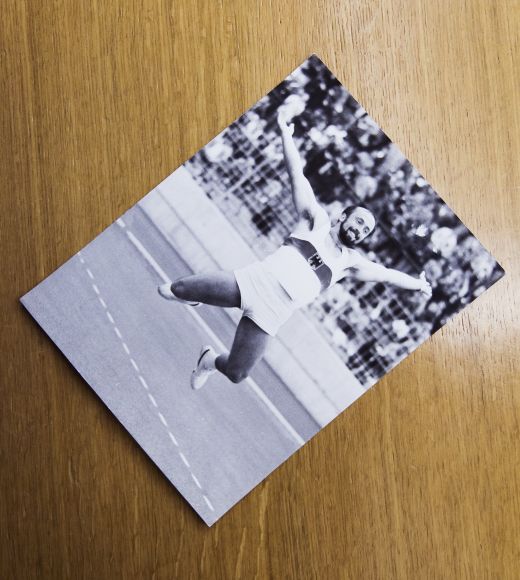

The victory leap: at the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972, Klaus Wolfermann defeated the top-rated world record holder Jānis Lūsis in the javelin throw and won the gold medal (Picture: private).

I had already trained a few times in the new Olympic Stadium in Munich before the Olympic competition and I won the German Championships there. In that stadium back then, just as it is today, it was very difficult to throw javelins because of the plastic roof. The wind comes in over the stands and causes turbulence under the roof. The javelin only flies properly if you throw it at a particular angle. I had discovered that beforehand. There was a scoreboard on the other side and a clock just below it. That was the fixed point for me. Of course, I had told the other athletes – I didn’t just keep this information for myself.

So you aimed for the clock?

I fixed my gaze on it as I threw. In the “crossover” phase, your body tenses and builds up the energy for the throw. But you must keep your eye on the tip of the javelin and it must point in the direction that then determines the angle of the throw. For me, the tip was pointed exactly to this clock. That was a throwing angle of about 32 degrees. This sent the spear on a long trajectory.

And that’s exactly how you threw your victory shot?

I was so motivated on that day, I had a scary level of concentration. Friends were standing behind me screaming and roaring, but I heard nothing. Nothing. I had my shutters battered down and I just barreled through my throws like a madman. On my fifth try, I risked it all. I extended my run up by a few meters, I went faster, a huge risk – I could have collapsed like a house of cards in the throwing phase. As the javelin went off I sensed how far it would go – it was perfect. I knew it was going a long way. The scoreboard then confirmed that: 90.48 meters.

But your rival Jānis Lūsis had the next throw.

I experienced a sense of great fear and hope and everything mixed together. But his throw was two centimeters short of mine. At first, there was an explosion inside me – a pleasure, an outburst of joy. It has to be said that there was a very important factor in my victory: it was the first time that digital measurement was used. You can imagine, if they had used the tape measure like they used to – what with the molehills, bumps in the ground – it might have come out differently. Afterwards I got a copy of the report: it was exactly 2.02 cm. Unbelievable.

What was your first reaction to the victory?

I was in a state of shock. I went over to Jānis Lūsis first and apologized for winning. “That was not planned,” I said. He was clearly disappointed, no question, but he bore it with dignity like a great competitor. We have been friends ever since.

Were you often recognized on the street after that?

You bet! I went on holiday immediately and when I got home, there were mountains of letters asking for autographs. You have to get used to it – it’s a completely different life. There were photoshoots without end and one interview after another. It was difficult because I had to continue in my job, to find normality again. But normality – that never really came back.

You continued your athletic career as a competitive javelin thrower but then you suffered a serious injury. How was that?

May I say the Bavarian word beschissen (crappy)?

You may.

I invested too much ambition in the years after 1973. After my world record of 94.08 meters, which I achieved one year after my Olympic victory, I thought it would go on and on. But I exceeded the limits of my resilience. It was a week and a half before the Montreal Olympics. At the last competition before in Zurich, I achieved equalization and I was putting on my clothes afterwards when I suddenly felt a sharp pain in my elbow. Part of the bone had been chipped off and it had become trapped. Surgery was the only thing that could be done. I unfortunately experienced the Montreal games in front of the TV. After that, I threw for another two years, but then it was over.

The whole thing is never quite over with you, though – you then competed in the bobsled and in car racing.

I decided to try as many sports in my life as possible. And when I like one, I keep doing it a bit longer. That’s always what I do – it’s the theme of my life. I want to test how far I can get with the abilities that God has given me.

Is your family also sporting?

My wife was a springboard diver and my daughter did a lot of athletics and rode horses. When she was training in athletics, my daughter was often asked teasingly, “You’re a Wolfermann and you can’t throw?” But she was very good at running and jumping, a good hockey player, an excellent skier. Today I do a lot of sports, often with my granddaughter. We have a very close relationship.

What do you do together?

She plays golf with me, for example. I have to make an effort now, she has gotten so good. Whenever her school day ends two hours earlier, she calls me and says, “Grandpa, pick me up, we’re going to go skiing in Garmisch.” And now she even helps me with my events and fundraising events.

What events are those?

After my active sports career, I had a very successful 13 years at Puma as the head of promotion. After that I founded my own agency. We are still organizing events to this day, especially for the KiO-Kinderhilfe Organtransplantation (charity for organ transplants for children).

The quiet life of a retiree is not for you?

The work is incredibly fun. I do it with my wife and it keeps us young. I’m lucky to be part of a community of former athletes who are very involved. At each event, I have between eight and 15 prominent individuals of my generation who support me. I really take my hat off to them.

Athletes such as the former handball professional Heiner Brand and the high jumper Ulrike NasseMeyfahrt come because they are inspired by the cause. What motivates you to organize these events?

The most important thing for me is that we can help others who are worse off than us. When you see all the things that children can do again after a successful organ transplant, including sports, with their eyes sparkling, it’s really fantastic. We have secured 3.5 million euros to this end solely through our activities in recent years. I think that’s a very worthwhile thing and a good story. Everyone helps together, my granddaughter as well. Lovely, just lovely. If this continues, it’s more than I can wish for.

Klaus Wolfermann (Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM).

Klaus Wolfermann

State approved freelance physical education teacher 1968

Klaus Wolfermann completed his training as a freelance sports teacher at the Bavarian Sports Academy (BSA), which was integrated into the TUM in 1972. His greatest athletic success was victory in the javelin competition of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, where he defeated the highly favored world record holder Jānis Lūsis with a throw of 90.48 meters.

Klaus Wolfermann was German champion in the javelin six times in a row. He was proclaimed German Sports Personality of the Year in the Federal Republic of Germany twice and European Athlete of the Year once. After the end of his career as a javelin thrower in 1978, Wolfermann was active as brakeman and pusher in bobsled and in 1979, in the four-man crew under the pilot Georg Heibl, he achieved German runner-up and fourth place in the European Cup. Klaus Wolfermann’s fame attracted the interest of sporting goods companies.

In 1980 he accepted a position as head of the promotion department at Puma and he travelled around the world in this role. Klaus Wolfermann ran a sports marketing agency and was the chairman of FC Olympia, an association of German medal winners who participate in football, volleyball, golf and other events for charitable purposes.

He was an ambassador for the Special Olympics, the only IOC-authorized sports association for mentally handicapped people. He was also an ambassador for Munich’s 2018 winter Olympics bid. He has been married to his wife Friederike since 1967.

Klaus Wolfermann died on December 18, 2024 at the age of 78.