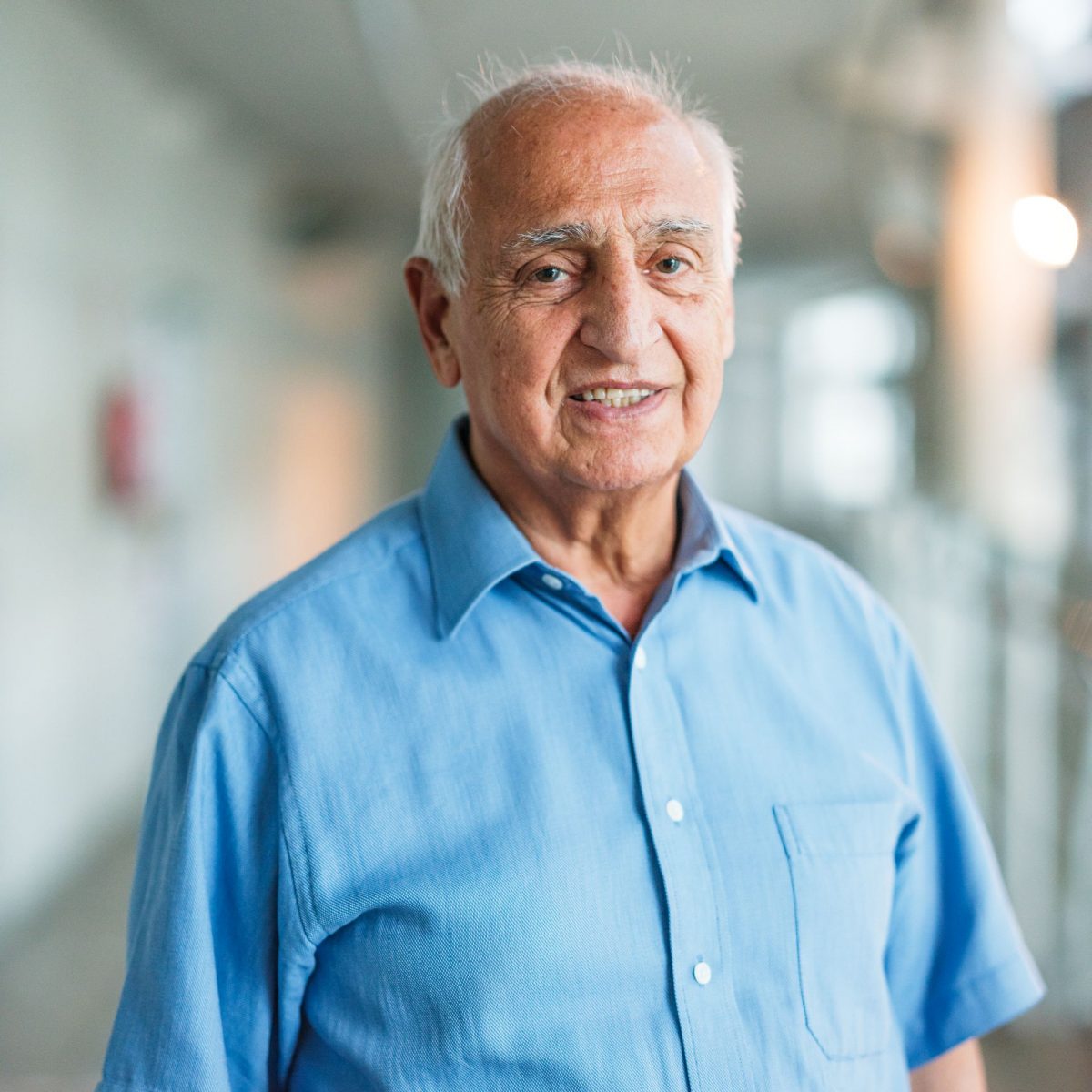

TUM Almnus Dr. Farhad Farassat is now a member of the TUM University Council and is involved in numerous student projects as an advisor. In 2021, he was made an Honorary Senator of TUM in recognition of his many years of service (Image: Alexander Gerner/TUM).

Today, around 40 years later, he is using the proceeds from the sale of his company to support students at TUM through the Deutschlandstipendium. Farassat also serves as a student advisor and draws on his experience to assist the TUM University Council with decisions affecting the future of the university.

We met the generous benefactor and Honorary Senator along with current TUM student Paula Ruhwandl. She currently holds a Deutschlandstipendium scholarship financed by Farhad Farassat.

Farhad Farassat: We were impressed with Paula from the outset. She’s a talented young woman with wide-ranging interests and talents. In addition to her studies, she’s also a coach at her rowing club. And you have a job as well, don’t you?

Ruhwandl: That’s right. I’m currently a working student in the semiconductor industry. I learn a great deal there. At the same time, I’m pleased that the Deutschlandstipendium means I don’t have to rely on working alongside my studies to get by. It’s important to me to be able to stand on my own two feet and I hugely enjoy my volunteering activities. Rowing provides me with good balance and also presents a challenge. As a coach, I have to lead and motivate my team.

Farassat: That’s exactly what we wanted to achieve with our funding: for young people to be able to pursue their interests and passions, furthering their skills in different ways, including away from their studies. Paula isn’t our only scholarship holder – in fact, we’ve meanwhile funded around 90 scholarships at TUM.

Dr. Farhad Farassat is not only a sponsor, but also a mentor for Paula Ruhwandl (Picture: Alexander Gerner/TUM).

Ruhwandl: And so why did you move to Germany?

Farassat: In Iran, we were always told that German mechanics is the best in the world. Obviously, I wanted to see if it was true! (laughs)

Ruhwandl: My father’s a German engineer, so he’d probably agree with that assessment! (laughs) But did you find that to be the case during your time at university?

Farassat: I had wanted to all my life. Even as a child, I was a very talented mechanic. For instance, I built little carts, which you could propel using foot pedals. And bicycles, too – they were made from wood, of course, and didn’t work. (laughs) But I had the ambition to create something. I always wanted to figure out how things work, so whenever a mechanical device broke, I would unscrew it straight away to see if I could repair it. From a very early age, I was endlessly fascinated by mechanics. So, it was obvious to me that I wanted to learn more about it.

Ruhwandl: And so why did you move to Germany?

Farassat: In Iran, we were always told that German mechanics is the best in the world. Obviously, I wanted to see if it was true! (laughs)

Ruhwandl: My father’s a German engineer, so he’d probably agree with that assessment! (laughs) But did you find that to be the case during your time at university?

Paula Ruhwandl has already successfully completed her Bachelor's degree in Electrical Engineering and Information Technology at TUM and is currently studying for a Master's degree. She is recently receiving a Germany Scholarship sponsored by Dr. Farhad Farassat (Picture: Alexander Gerner/TUM).

Ruhwandl: Why not?

Farassat: As an engineer, the larger the company, the less influence you have on the overall product as a whole, the machine as a whole. In very large companies, the few engineers they have are so specialized that they often only develop small components, perhaps two screws for a specific machine. For me, though, it was always very important to be able to see and work on the whole product.

Ruhwandl: What field was your company in?

Farassat: We specialized in microwelding technology. It’s used in the manufacturing of computer chips, for example – which you deal with in your working student position. By chance, I had visited a company that was active in the microwelding field. Its equipment was not computer-assisted at that time, so everything had to be operated manually. So, you would have a woman sitting there welding together individual wires that were only 25 μm thick. It wasn’t really possible to see it with the naked eye: even if you were fully concentrated, the welding was still very imprecise. It was clear to me that we needed to develop something to automate the process. That’s why I came together with my business partners and built the world’s first fully automatic microwelding device.

Ruhwandl: Just like that?

Farassat: Nothing’s ever as easy as it sounds! (laughs) But we knew that, together, we could find a solution. And we were absolutely determined to do just that. So, we pooled our expertise, tried out a lot of different things, and learned a little more with every model we made. I was driven by my curiosity – and the wealth of knowledge I had acquired at TUM certainly helped, too. And, in the end, the project was a success.

Ruhwandl: How big was your company?

Farassat: When things were at their best, we had around 150 employees. I wouldn’t be where I am today without them. My company was always like a family to me. It was important to me that my employees were happy and well. I always felt that a first-rate company culture was crucial. So, when I came into work in the morning, I would greet the employees personally before anything else. That way, I could see for myself if someone wasn’t doing well or needed help.

Ruhwandl: I already notice that as a working student. It is very important to be recognized on the job and a good atmosphere in the company plays a decisive role.

Farassat: A first-class corporate culture has always been of central importance to me. When I came into the company in the morning, I would first greet the employees personally. That way, I could immediately feel if someone wasn’t feeling well and needed help.

Ruhwandl: That’s really impressive. I think we need more role models like that.

Farassat: In 2001, I was named Entrepreneur of the Year in Germany. I was the first foreigner to win this title in Germany’s industrial segment. To this day, I’m very proud of this.

Ruhwandl: Including student projects?

Farassat: Yes, I’m really excited to support the TUM Autonomous Motorsport team, for example. Its dedicated students and doctoral candidates are developing an AI-controlled race car capable of reaching top speeds up to 270 km/h. I think it’s sensational. Sitting down with young people, advising them on their project and sharing my opinions and experiences with them on certain issues is something I find hugely enjoyable. The students working on the project are motivated and very hardworking. It’s wonderful to see.

Ruhwandl: Not only does Dr. Farassat support me financially through the Deutschlandstipendium, he also stands at my side as my mentor. It’s heartening. I know that I can contact him at any time with questions about my studies or my career choices. I’m sure I’ll benefit a great deal from his wide-ranging life and professional experience in the future.

Picture: Alexander Gerner/TUM

Master´s in Mechanical Engineering 1974, Nuclear Engineering 1977

Farhad Farassat moved from Iran to Munich in his early 20s and studied mechanical engineering and nuclear engineering at TUM. He received Master’s degrees in both subjects and, shortly after graduating, joined forces with two other partners to found a company specializing in microwelding technology for computer chips. In 1992, Farhad Farassat acquired the company in a management buy-out together with his classmate Said Kazemi and became head of the company.

In 1997, the TUM Alumnus received his doctorate from TU Berlin on the topic of bonding process controls. In 2001, he was named Entrepreneur of the Year by German publication Manager Magazin. In 2016, he sold the company and resolved to donate 20% of the proceeds to TUM – with a portion donated to the University Foundation and the rest set aside to finance numerous Deutschlandstipendium scholarships. Dr. Farassat remains active at TUM to this day, contributing to the TUM University Council and advising a host of student projects. In 2021, he was named an Honorary Senator of TUM in recognition of his services.

TUM-Deutschlandstipendium holder Paula Ruhwandl

Bachelor’s in Electrical Engineering and Information Technology 2022

Paula Ruhwandl was born and raised in Munich. She has already completed her Bachelor’s in Electrical Engineering and Information Technology and is specializing further in her Master’s studies. She is gaining experience as a working student at Infineon and is a volunteer coach at her rowing club. Currently, she holds a Deutschlandstipendium funded by Dr. Farhad Farassat.